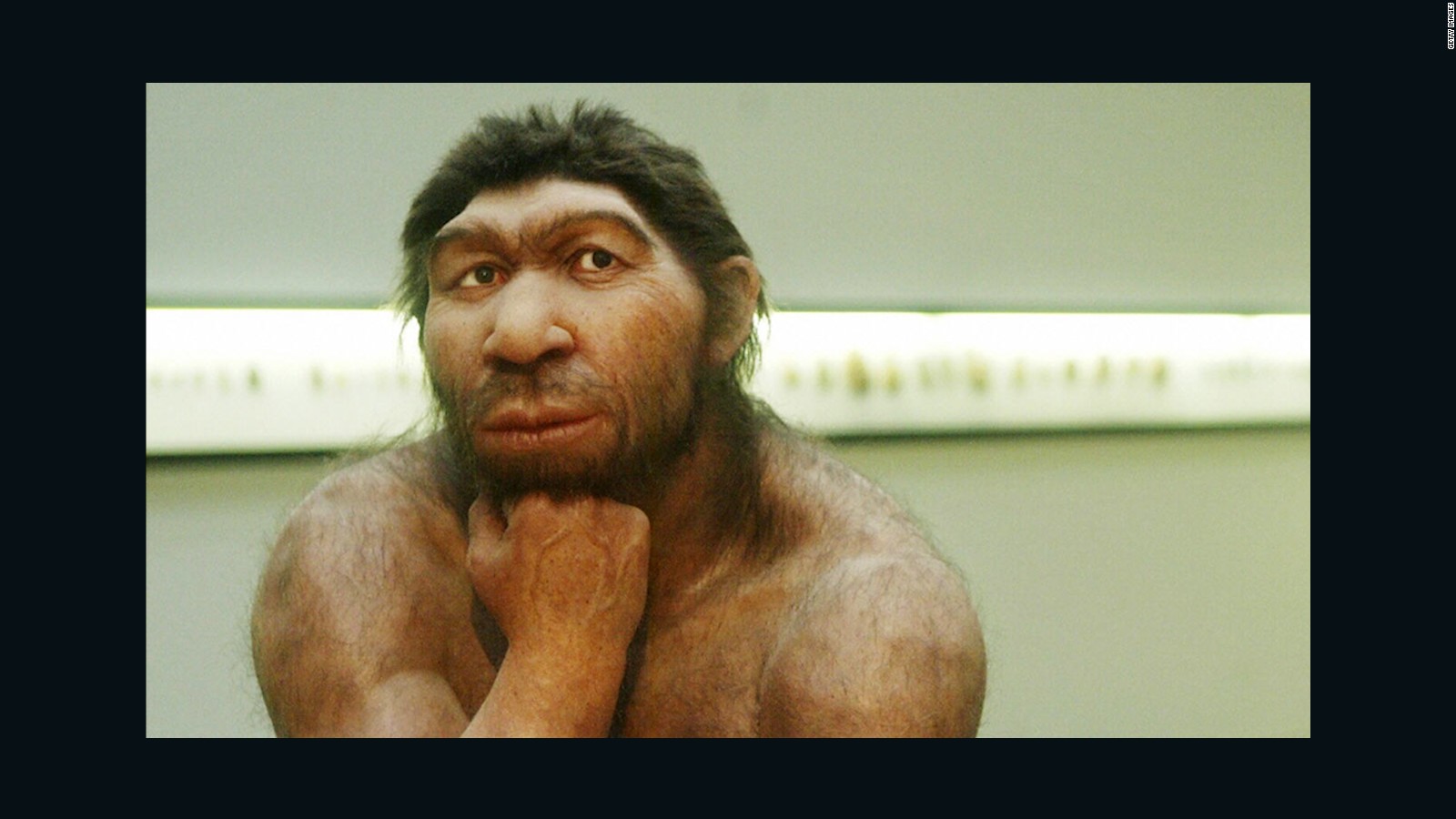

Got allergies? You can blame the Neanderthals 01:31

Story highlights

- Analysis of genetic information worldwide found that some people had blends of archaic DNA

- Traces of Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry was found in some Pacific Islanders

(CNN)Neanderthals may not have been as lucky as our human ancestors in the long run, but that doesn't mean the two subspecies didn't get lucky.

Scientists

have discovered that Homo sapiens -- that's us -- made more babies with

archaic humanlike species than initially thought. That sexual history

has left a mark on the human genome, possibly influencing our immune

systems and metabolism, according to a new study published in the journal of Science.

Scientists

analyzed the genetic information of more than 1,500 people from all

around the world and determined that ancestors of modern humans

interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

They learned that some Asians, Europeans and even the Melanesians of Papua New Guinea had Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry.

Mystery

surrounds the Denisovans, which were related to Neanderthals but

genetically different, in much the same way Neanderthals were distinct

from modern humans. In 2008, fossil remains of Denisovans were

discovered in a cave in Siberia.

The

discovery of traces of Denisovan DNA in the people of Melanesia is

significant because the Pacific Islanders live thousands of miles away

from the Siberian region that Denisovans are believed to have existed.

"It

is still not exactly clear when and where Melanesian ancestors crossed

paths with Denisovans, but our best guess is somewhere in mainland

Southeast Asia," University of Washington evolutionary geneticist Joshua

Akey, who helped lead the study, told CNN.

This is a likely scenario based on the low levels of Denisovan ancestry found in some South Asian populations.

The

study confirms early theories that our human ancestors interbred with

other hominins after they left Africa more than 50,000 years ago.

"What

was surprising from our study is that it revealed the history of

contact with Neanderthals was more complicated than previously

anticipated," Akey said.

And those

sexual encounters may have played an important role in bestowing humans

with biology that impacts our skin and hair, giving us

infection-fighting advantages. "Many of these genes are involved in

immunity and likely helped our ancestors fight new pathogens that they

were exposed to as they dispersed into new environments," Akey said.

The

research discovered that all non-Africans who were analyzed in the

study had traces of Neanderthal, and different groups from Europe, Asia

and Melanesia had distinctive blends of Neanderthal genes, which likely

means humans repeatedly ran into these hominins, according to Benjamin

Vernot, a postdoctoral student in genomic sciences at the University of

Washington, who led the project.

"Studies like ours help to better understand the sources contributing to patterns of human genomic diversity," Akey said.

This study gives scientists new clues about the archaic DNA that may have influenced traits in modern humans.

Comments

Post a Comment